SELF-PROPELLED ARTILLERY

Part 1 by BRYAN PERRETT

Start of a series on Self Propelled weapons which he describes early

British, French and German examples.

THE BUSINESS OF artillery is the destruction by missiles of predetermined targets, and is an exact science which has evolved since the days when gunners were the only professional troops in the service of a medieval monarch. The artilleryman’s principal weapon is, of course, the gun. This is used against troops in the open, in counter-battery work, and for battering at the walls of buildings or fortifications.

There are, however, many occasions when a gun cannot be brought to bear on a target because of features intervening, such as crests, woods and buildings. The target cannot be engaged simply by elevating the gun, as the muzzle velocity of the weapon would ensure that the round merely over-passed the obstacle, but also the target as well. The answer to the problem lay in the design of a shorter weapon which was capable of high-angle fire at a low muzzle velocity. This weapon was, and still is, known as a howitzer, from a German word meaning ‘roaring beast’. In addition to the benefits conferred by the howitzer’s ability to engage targets in dead ground, experience proved that it was also most effective against troops seeking protection in field works or buildings, where its high trajectory enabled shells to penetrate a trench or roof and explode inside. Another type of high-angle weapon is the mortar, which has a very short barrel in relation to its calibre.

This is employed against fortifications, heavily defended buildings and strongpoints, where it is desirable to crack open the structure by means of heavy explosive shells landing on the weakest part of the structure, usually the roof. The gun, the howitzer and the mortar are, then, the basic weapons of the artilleryman, and all have been reproduced in self-propelled versions. There are other forms of self-propelled gun, notably tank destroyers and antiaircraft tanks., which might be manned by artillerymen, but these vehicles have been designed for specific roles, and we shall confine ourselves to those vehicles which have been built primarily for the artillery’s general purpose function, the overall support of the other teeth arms. The self-propelled gun, like the tank, was born as a result of the conditions prevailing on the Western Front during World War I. It will be recalled that at this phase of military history, because of the machine-gun and barbed wire, defence was stronger than attack, and that the massive infantry assaults were frequently preceded by a long and intense artillery preparation.

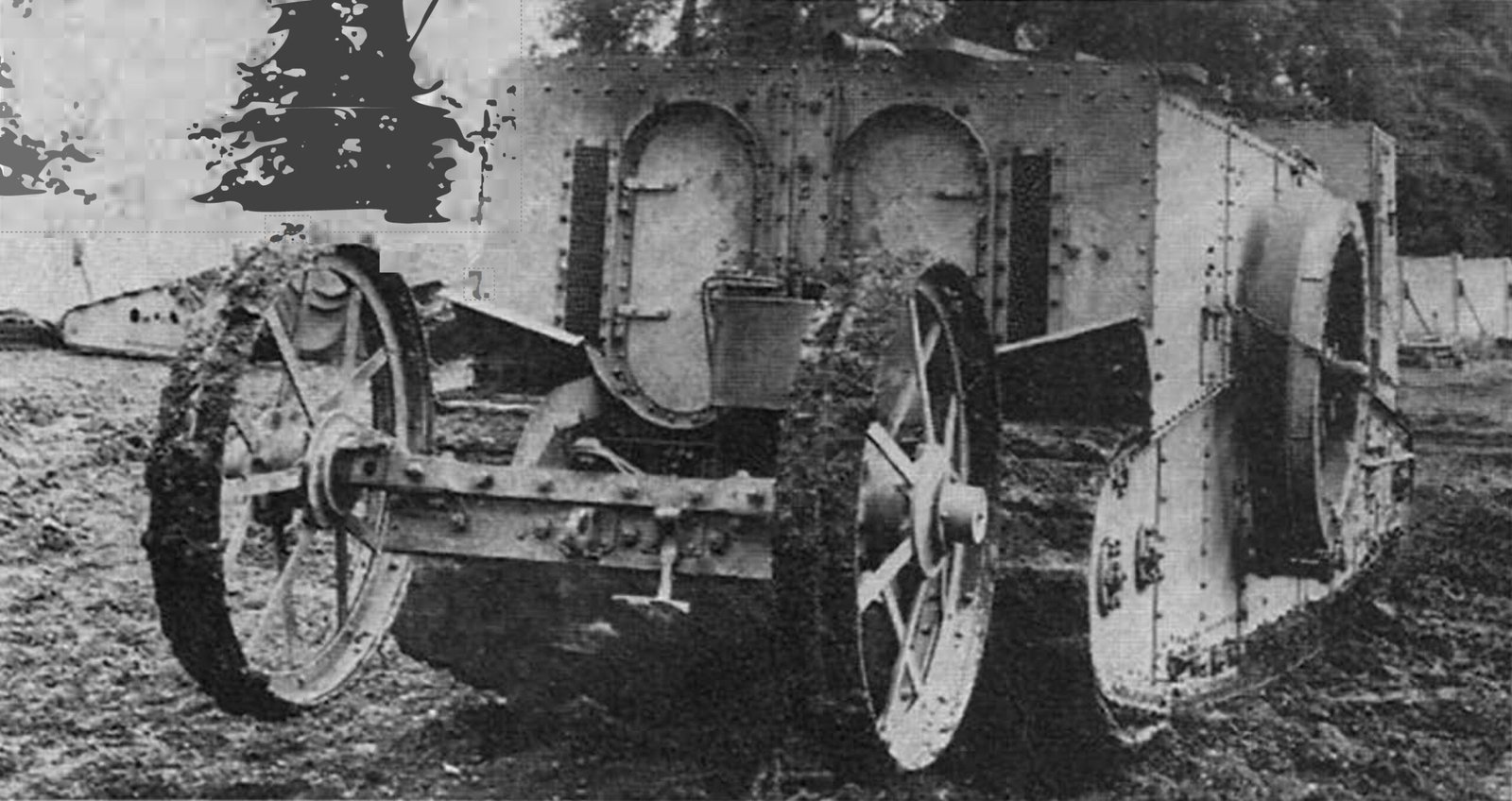

This had the effect of completely destroying the surface of the ground in No Man’s land and beyond the enemy’s front line, with the result that even if the infantry assault was successful, supplies and guns could not get across to protect and reinforce the newly-won front line. As troops relied upon their own artillery to break up an impending counter-attack, this situation was obviously very serious. A far-sighted and feasible solution was found in the Gun Carrier Mark I, a vehicle which employed many of 1he parts of the Tank Mark I, including the trail wheels, although these were ultimately discarded.

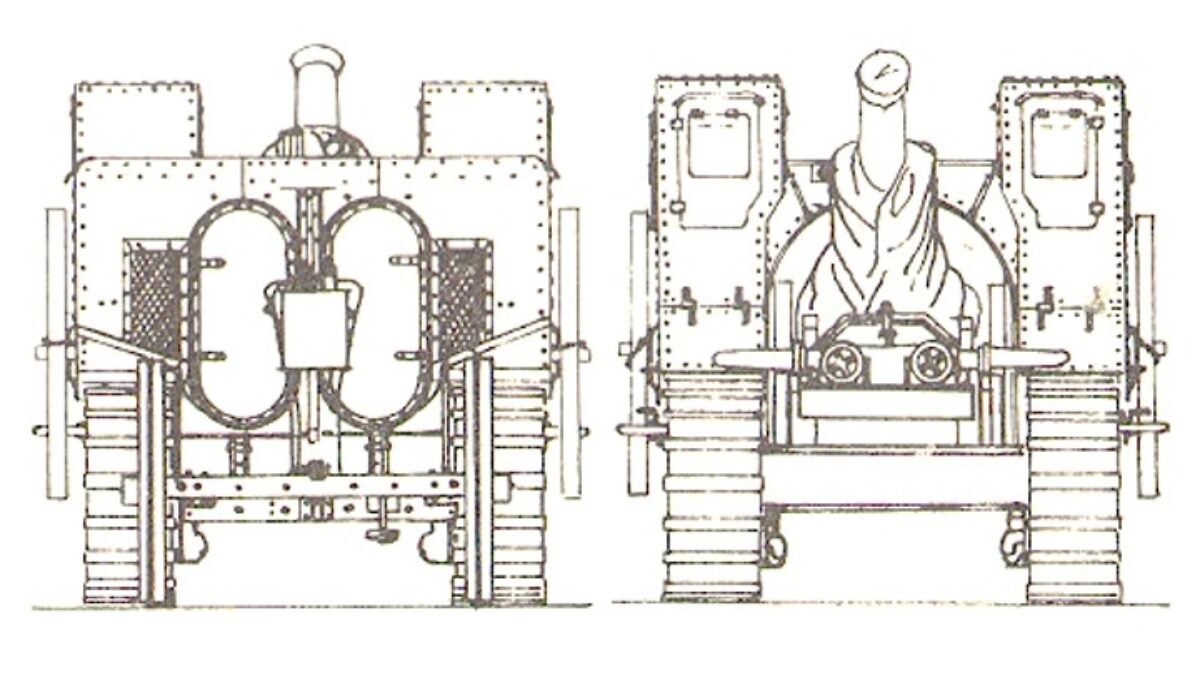

Layout differed from that of the Tank Mark I in that the tracks did not wrap round the whole vehicle, the engine and crew compartment consisted of an armoured box at the rear, and the driver and brakeman were housed in individual armoured cabs mounted over the front horns. Between these cabs was a ramp up which the weapon could be winched. The wheels from the piece’s carriage were removed and slung on either side of the Gun Carrier. Either a 60-pdr. gun or a 6 in. howitzer was carried. Technical difficulties prevented

The British Gun Carrier Mark 1 features in the illustrations on this page; it was based loosely on the Tank Mark 1 and. sadly. its potential was never properly exploited.

the firing of the 60-pdr. gun from the Gun Carrier, although several of these weapons were delivered forward during the Third Battle of Ypres. The 6 in. howitzer was, however, used from the carrier, in a most ingenious way. In a war as static as the Western Front of 1914/18, each side was able, because of the aeroplane, to plot the positions of the other’s battery emplacements and record them on their maps. Counter-battery firing therefore became a matter of routine, each side being aware after a very short period which enemy battery was firing and required silencing.

During several night actions, German artillery observers were shocked to be on the receiving end of fire from not one, but several, unrecorded battery positions, against which retaliation was not possible. What was happening was that Gun Carrier batteries were being driven into position after dark, were engaging their targets, and were then moving on to new positions. Sad to say, these imaginative experiments did not find favour with the conventional artillerymen, who, like the cavalry, preferred to keep their horses, and regarded the petrol engine and armour as temporary expedients brought about by unusual circumstances.

The two-gun carrier companies, with a total of 48 vehicles, were converted to a supply role, and a weapon system, which, employed correctly with tanks and infantry, could have been a battle winner, was thus reduced to the status of a pack animal.

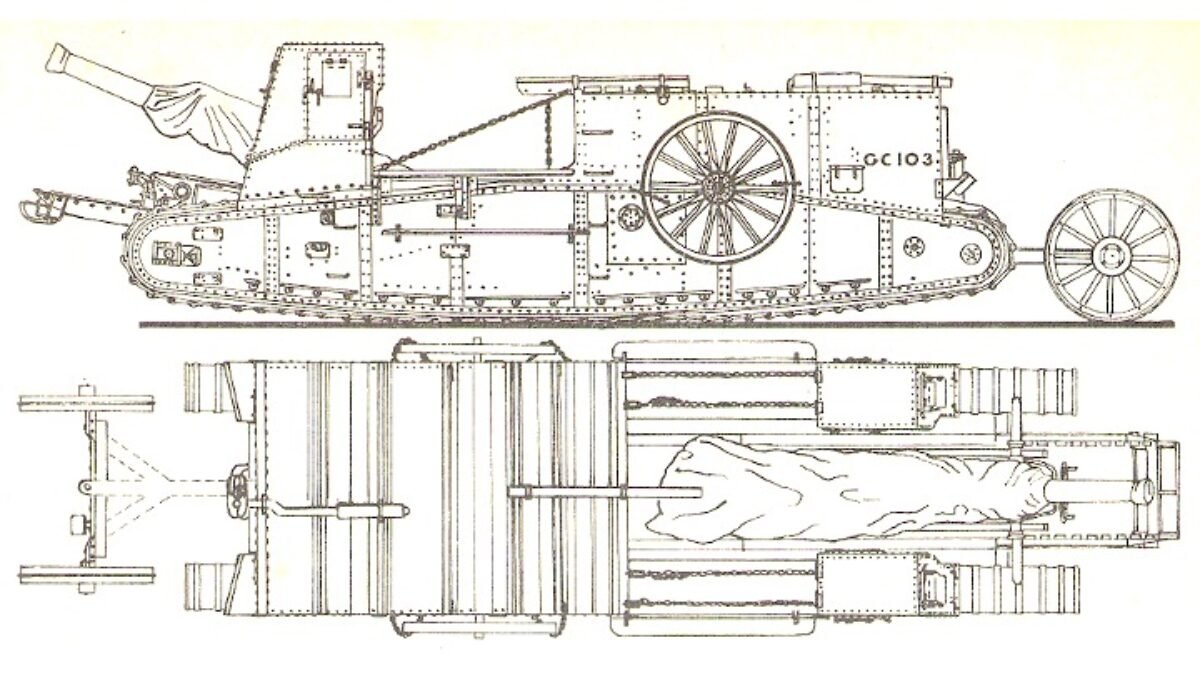

The French army had also shown an interest in self-propelled artillery, and, in fact, had produced several prototypes by the end of the war, employing the chassis of the St. Chamond, Schneider and Renault FT tanks to carry pieces varying in calibre from 75 mm. to 280 mm.

However, the opposition to change was as great in France as it was in Great Britain, the traditionalists protesting that immobilisation of the gun carriage for any reason would prevent the piece taking its place in the line, or cause its loss, a criticism which could not be levelled at the towed gun, whether the motive power was provided by a tractor or a team of horses. This, of course, reflected the traditional code of the professional artilleryman, who had been brought up to believe that it was disgraceful to fail in bringing up one’s guns where they were most required, and worse still to abandon a piece on the field of battle in an undamaged state.

a French Canon Automoteur de 194 mm. reversing into a hide; based on the St. Chamond tank chassis which was itself based on the Holt Caterpillar tractor. Many were captured by the Germans and utilised unmodified.

Photo courtesy E. C. Armies

The conservative school of thought prevailed, and production stopped, although several 194 mm. self-propelled guns served with the French army early in World War 11, until captured and were used without modification by the Germans. This rather heavy looking weapon was mounted on the chassis of the St. Chamond tank, which was itself derived from the Holt Caterpillar tractor. No ammunition was carried on board, this being brought up by tenders, some of which themselves used the St. Chamond chassis. The British and United States armies also carried out somewhat half-hearted experiments with self-propelled artillery during the inter-war years, but the climate of the times was against innovation in military spheres, and they came to very little.

The German army was not so sanguine in its approach. As well as analysing the reasons for its defeat, it was also accepting the new concepts of armoured warfare which were being propounded by General Fuller and the late Sir Basil liddel Hart. It was quite apparent that if the Panzer Divisions were to be moved about in the intended manner, their supporting artillery must be equally mobile. Sheer physical exhaustion ruled out the old horse teams (it must be remembered that a large proportion of German artillery remained horse-drawn throughout

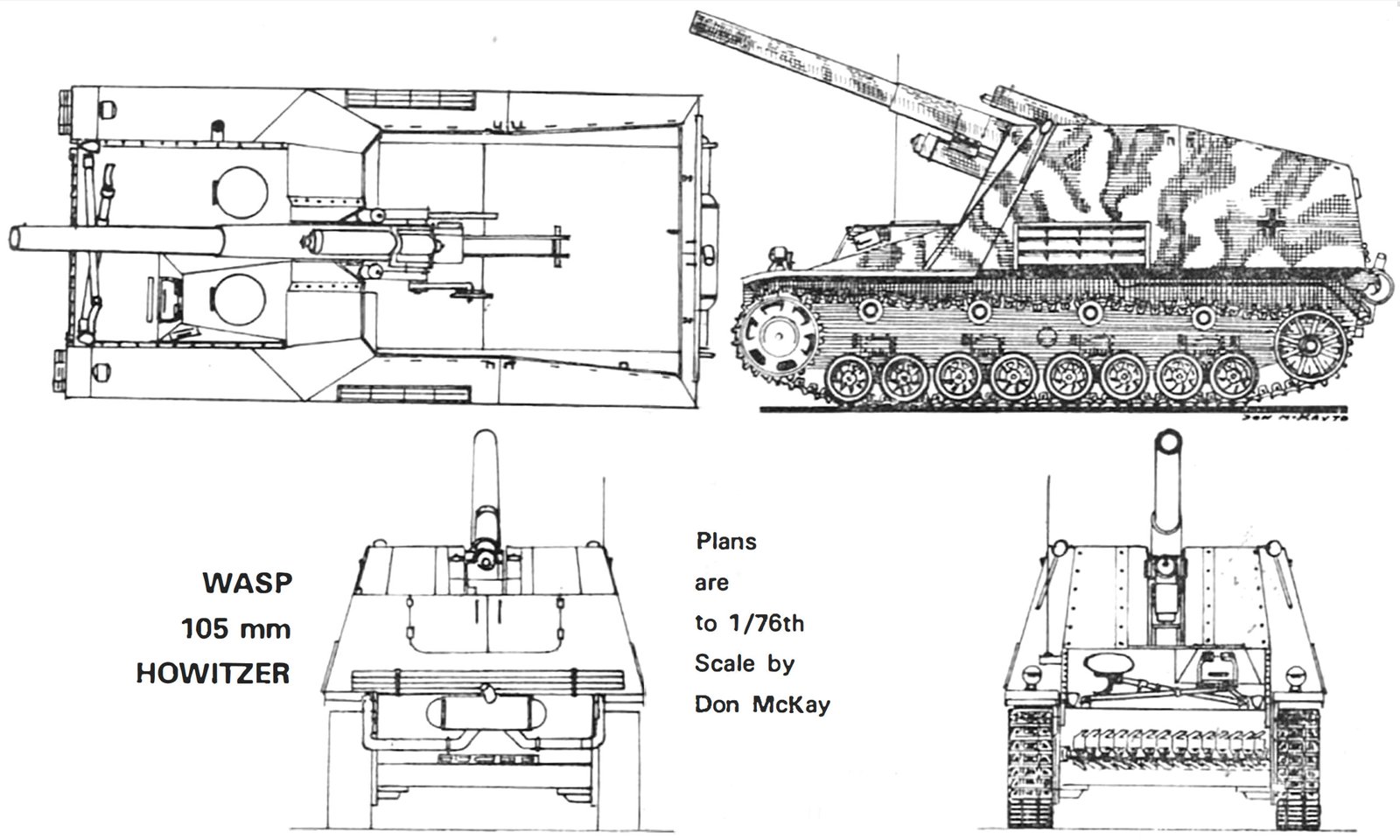

The Wasp 105 mm. Howitzer

World War II) and guns towed by lorries lacked the cross country mobility of the tanks. Clearly, the answer lay in the production of a fully tracked weapon system. At that period, I.e. the late 1930s, the only suitable basis for such a project was the chassis of the PzKw I, a light tank which was becoming obsolete for combat, and which had largely been relegated to the training role.

The Model B version was chosen to carry the 150 mm. Heavy Infantry gun, which was protected by a very tall armoured shield, giving the whole arrangement a top-heavy look. This conversion overloaded the 6-ton chassis, and provided a very cramped fighting compartment. The vehicle was in service in time to take part in the Polish campaign and the Blitzkrieg in the West. The same weapon was fitted to a carriage provided by the chassis of the PzKw II when this tank became obsolete, and this proved to be a much more workable arrangement. Although the open-topped fighting compartment provided little protection for the five-man crew, there was more room to serve the· gun, and ammunition stowage was available above the engine decks. Some versions have a lengthened chassis with an extra pair of road wheels.

The vehicle saw service in Russia, and, in small numbers, in North Africa. Its low silhouette and general layout made the vehicle a useful utilisation of an obsolete tank chassis, and if the PzKw II chassis had not been required for another vehicle, it is probable that more would have been built. The other vehicle was the famous Wasp, which, together with its big brother Bumble Bee, was intended to fulfil the Panzer Division’s requirements for self-propelled artillery. The Wasp was equipped with a 105 mm. howitzer with muzzle brake, and it was planned that each Panzer Division should contain two six-gun batteries of these weapons.

The 105 mm. s.l.g. on P2Kw I chassis.

R.A.C. Tank Museum photograph are used throughout this feature except where noted.

The fighting compartment, consisting of thin angled armour plate, was mounted at the rear, and the rear wall could be lowered to extend the working platform. Ammunition stowage was limited to 32 rounds, too few for bombardment purposes, and weaponless versions of the same vehicle accompanied the Wasp batteries to provide replenishment. The 105 mm. howitzer could normally engage targets up to 12,000 yards, but by using a super charge this could be boosted to 14,500 yards for a few rounds. Almost 700 Wasps were manufactured, and production ceased only when the Red Army overran the assembly plant.

Plans are 1/76th Scale by Don McKay

Reproduced with kind permission of Doolittle Media – www.adhpublishing.com/ First published in Military Modelling Feb. 1971