Charles Buchanan considers ….

….’those darn shoulder blades‘

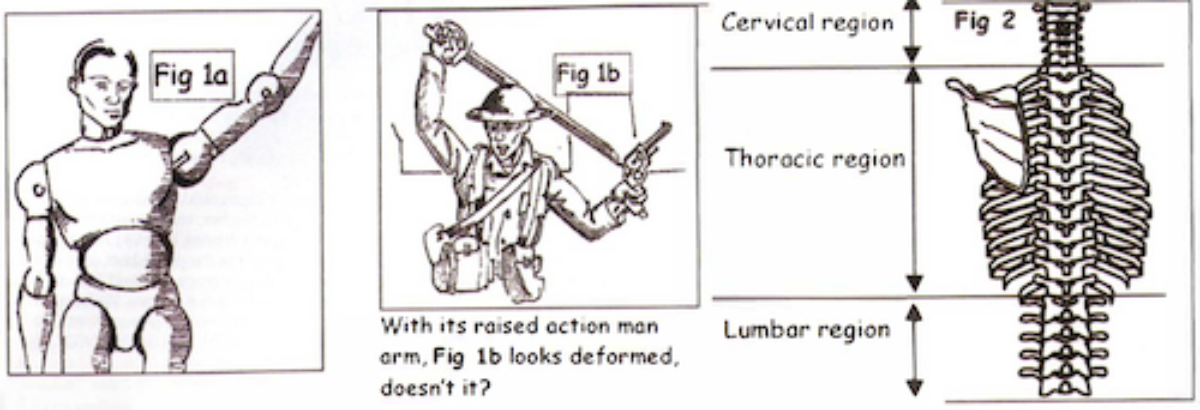

Of this I am sure, some inspiration for our art form is drawn from watching paramilitary action movies starring ‘pumped up’ actors, who spend hours each day in the gym honing out flawless physiques for the cameras. Inspired by these examples of human perfection, some modellers are inclined to channel such visions into their work, producing figurines with bulging biceps, chiselled abs, and waists so slim ‘Mi!.s America’ would be proud. In the real world body building is generally not a major part of a soldier’s life; all-round physical fitness and the ability to defend one-self with unarmed combat is of far more importance than ‘looking good!’ An athlete blessed with a well-defined body represents only a small portion of the general population, the rest of us coming in all shapes and sizes, far from what is deemed human perfection. From photographs I’ve seen of men engaged in combat situations, where tropical or desert heat warranted the stripping of

Because of the existence of bathroom mirrors, many of us know well what the front of our torsos look!. like, and this is often evident in our art, but what about our backs, much harder to model, huh? In fact it’s far easier to flesh out the front of a miniature figure’s chest, taking special care to alter the shape of a pectoral muscle because an arm is raised, than making sure posterior anatomy looks okay. ‘Those dam shoulder blades’ do present a problem if you’ve decided to create a busy mortar team or gun crew, stripped to the waist in the heat of battle.

Once again I apologize for technical stuff, but the purpose of this article is to help overcome modelling problems associated with posterior torso anatomy, and in particular the scapulae, or shoulder blades, us laymen call them. In short my goal is to help you to make your figures look more life like, with backs in proportion to physique, mood, and situation.

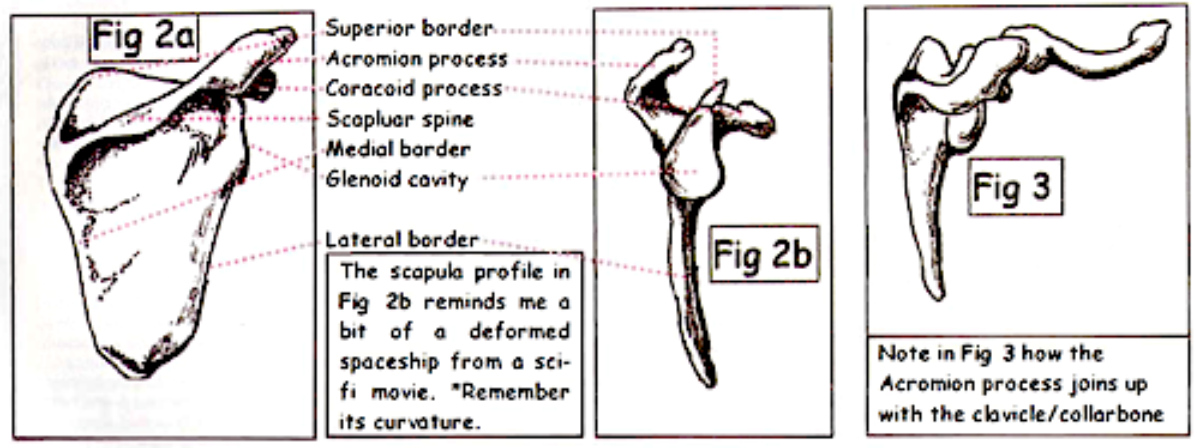

The shortcoming of these ‘toys’ is sometimes evident in converted figures.(Fig lb), promoting the incorrect idea that arms are directly attached to the ribcage, which they are not. In order for us to understand the shoulder joint, and without delving into too much textbook detail, we have to look beneath the surface at scapulae bones themselves (Fig 2).

The scapula or shoulder blade is a flat triangular shaped bone, (Fig 2a), with three borders, namely a lateral or outside border, a medial or inside border and a superior border or top.

The lateral border has a concave recess, (Fig 2b} called the glenoid Cavity. This’ is a sort of socket which the ball joint of the humerus bone fits and swivels, allowing us to rotate our upper arms and all those gestures – opposing spectators when we attend football or rugby matches. The scapula also possesses a spine, which begins on the upper medial side and works its way upwards and outwards ending in a curve called the Acromion process.

Immediately beneath and in front of the Acromion is another protrusion called the Coracoid process, both processes having distinct functions. The Acromion, which also protects the humerus, is connected via a ligament to the clavicle or collarbone, and the Coracoid via another ligament to the humerus, (Fig 3). As the arm is raised the scapula pivots, whilst the end of clavicle moves upwards accompanying this motion.

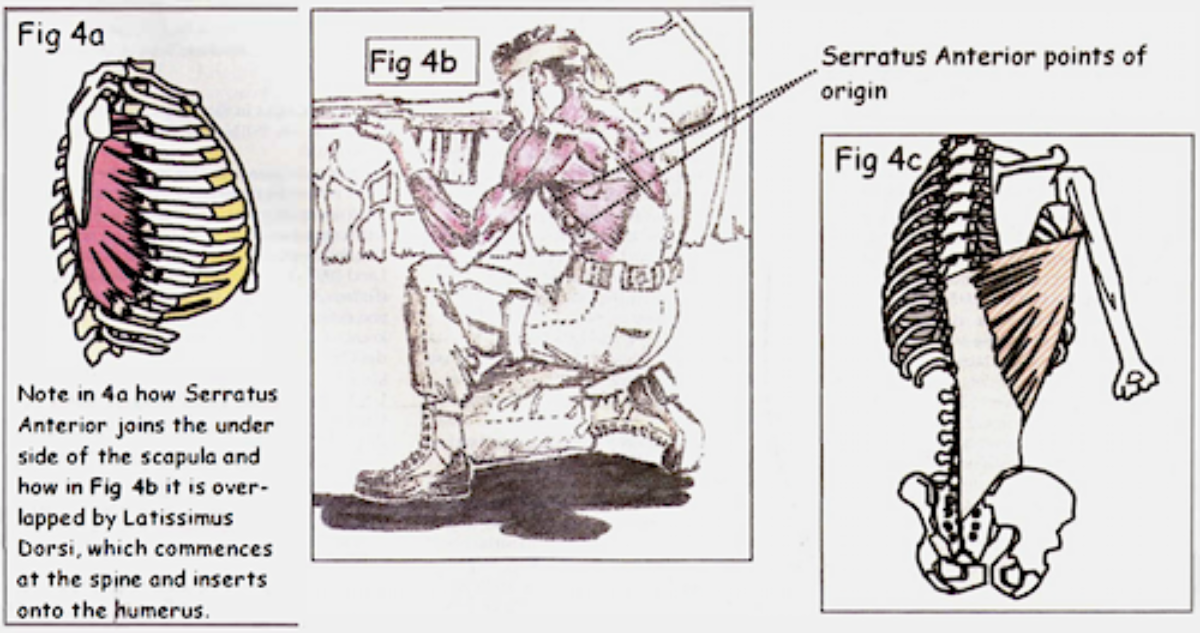

Now we must move on to some shoulder muscle action. Movement’,of scapula is controlled by a complete, array of shoulder muscles, one.of the most important being Serratus Anterior. This powerful muscle originates from the side of ribs 2-8, attaching itself underneath the scapula, (Fig 4a). Because muscle is elastic, and can, therefore, stretch and shrink, Serratus anterior permits us to hunch and stabilize our shoulders.

When a right-handed soldier aims his rifle, the left Serratus muscle allows him to hold and steady his rifle’s front grip’ (Fig 4b), lf you are modelling a figure strippcd to the waist with a hunched shoulder, you may wish to emphasize points of origin of this muscle but don’t forget, only its heads will be prominent, as most of the muscle is overlapped by Latissimus Dorsi (Fig 4c), or Lats as bodybuilders call. them.

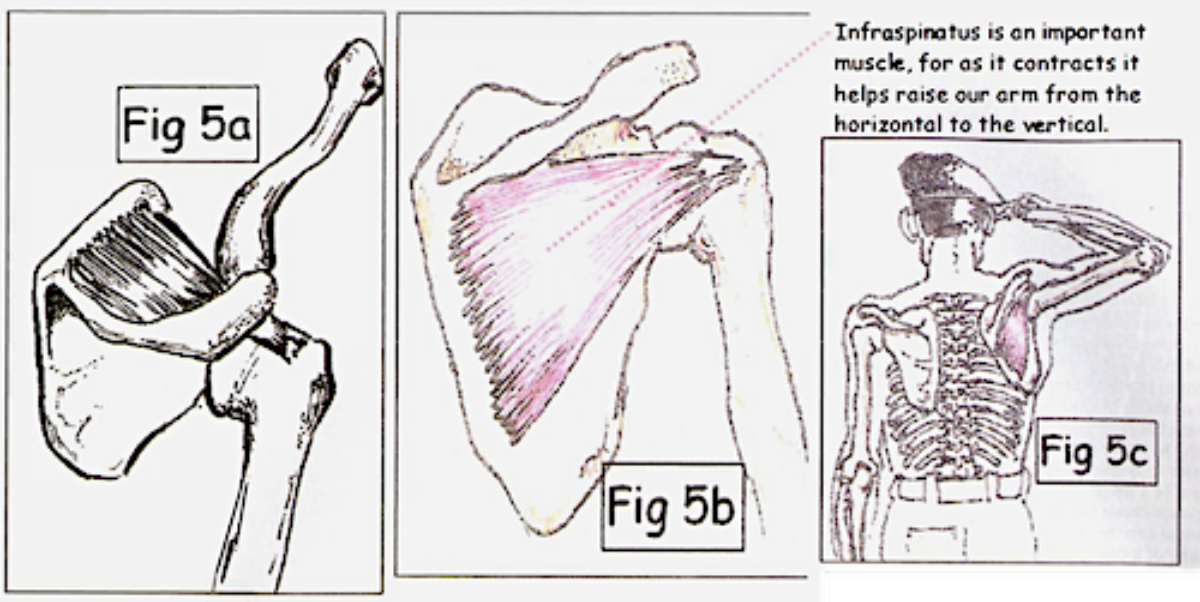

Before proceeding we must look at the scapula spine, as a dividing point for muscle attachments that have different functions. ‘Supra’ means above and a muscle that exists just above the scapula spine is Supraspinatus. Although it’s covered by a surface muscle and could be regarded as baggage.

I’ve included it because of its function. It passes under the Acromion process and attached itself to the top of the humerus, (Fig 5a), helping us raise our arms like the soldier saluting in (Fig 5c)

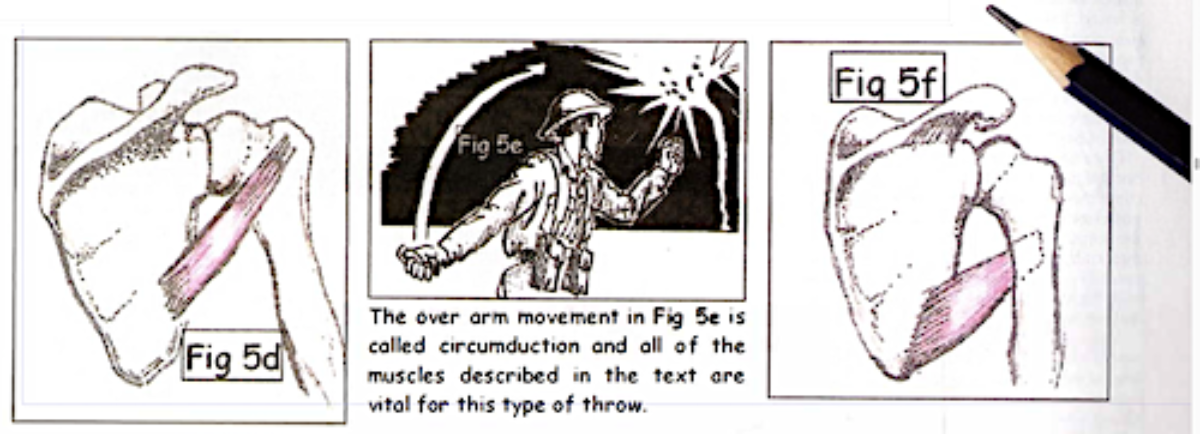

Infraspinatus sits below the spine and also inserts onto the top of the humerus (Fig 5b), Immediately below lnfrapinatus is Teres minor; (Fig 5d), these three muscles, Supraspinatus, lnfraspinatus and Teres

minor, forming part a foursome which make up the rotator cuff, allowing us, to make those circular movements, which a soldier would need in order to lob a hand grenade, (Fig 5e), or a bowler a cricket ball.

Teres major, which is not part of the rotator cuff muscle group, (Fig 5f), originates right at fhc base of the scapula, inserting on to the front of the humerus.

There are other muscles, which originate from the medial/inner side of the scapula that attach themselves to the spine and lower back. part of the skull, all of which counteract Serratus anterior by effectively pulling the scapula inwards and upwards.

Again, I won’t go into them because they’re hidden under other muscles and regarded by us as baggage. So to recap briefly, Supraspinatus is above the scapula spine whereas lnfraspinatus, Teres major and Teres minor are below, all inserting onto the humerus.

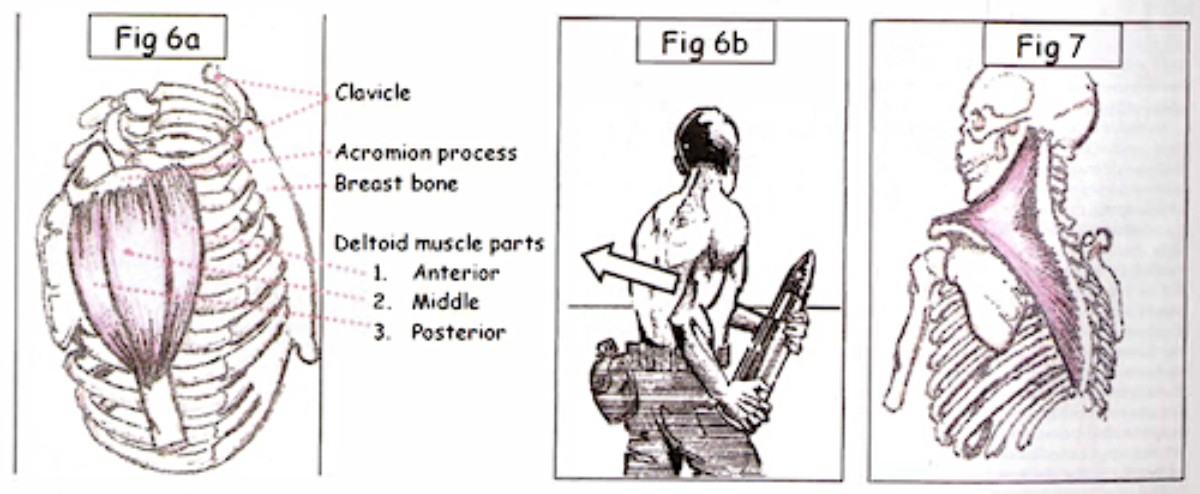

We all know where the Deltoid muscle is. It’s large surface layer shoulder muscle, which has three segments: back, middle and front. You’ll see this if you tense your arm in front of the bathroom mirror. Its back portion originates from the scapular spine, its mid portion .from the Acromion process and its front, two thirds of the way up the

clavicle’/collar bone, (Fig 6a). Deltoid’s posterior /back portion lies over roughly one third to half of lnfraspinatus, and muscles Teres major and minor.

A large surface layer muscle Latissimus dorsi, passes over the base of the scapula, and inserts onto the humerus, (Fig·4c). Latissimus helps pull our arm backwards as we march, run and swim, (Fig 6b)

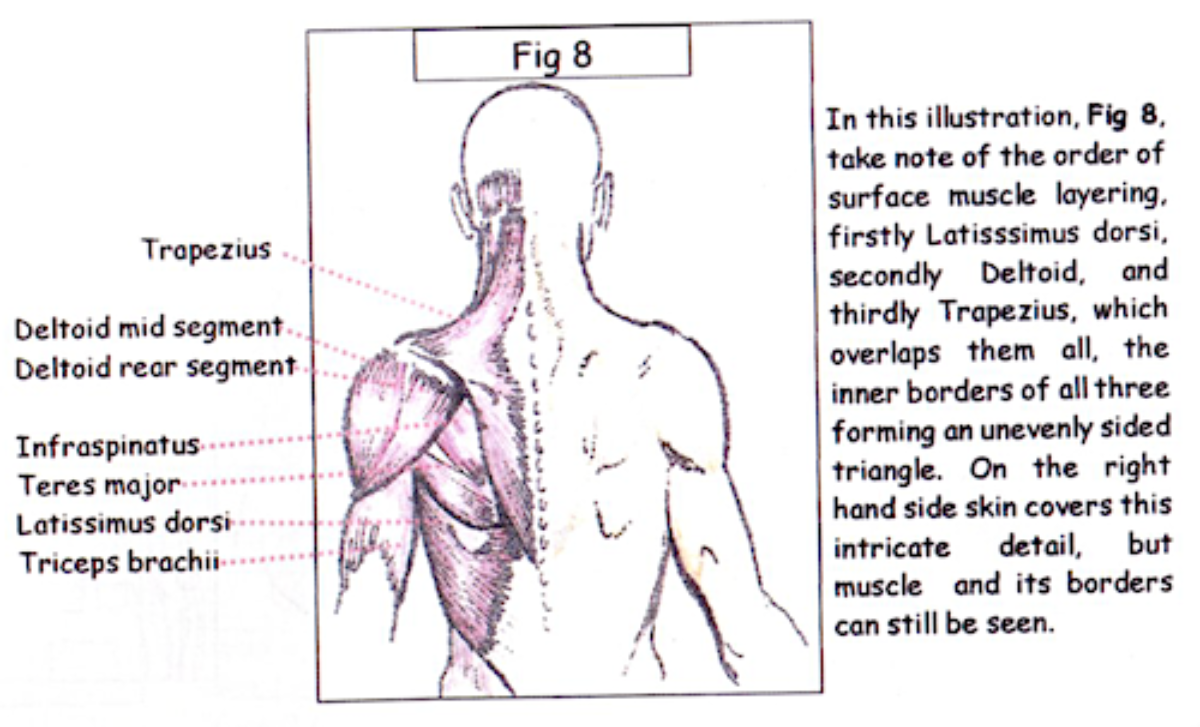

Trapezius is the last to deal with, (fig 7), a dagger-shaped pipe of muscles originating on both sides of spine , over lappjng Latissimus dorsi and rear segment of Deltoid as they insert onto the scapula spine. All three effectively form a triangle around the scapula, overlapping its three corners, (Fig 8) but in a specific order:

Latissimus Dorsi –Deltoid –Trapezius,

When flexed’; Serratus anterior is visible, and when extended lnfraspinatus, Tcrcs. major, and Trapezius become prominent. Remember to take this triangular shape into account when modelling a shoulder blade, how it overlaps and how two scapular muscles in particular, lnfraspinatus and Tcrcs major, become visible, and don’t forget that slight dividing line between the two.

In conclusion try a avoid over emphasizing musculature by modelling an average man’s scapular area. I know crafting bulging biceps is great when you’re young, and I distinctly recall going through that phase when in my teens, but as stated previously aim for a natural look, taking into account what muscles will be prominent when an arm is

extended backwards and what will be visible when it is flexed forwards. In y:cars to come you’ll appreciate this because naturalness in your work will render it timeless.

By kind permission of Doolittle Media. Originally published in Military Modelling