Resting

in

Action

Peace?

By

Dilip Sarkar MBE

A veiw of the completed project.

The colossal cost

During the First World War, some 38 million human beings lost their lives – for which shocking reason the unprecedented global conflict became known as ‘the war to end all wars’. Tragically it was not to be and, as a result of the subsequent Second World War, over 60 million civilian and military personnel lost their lives which was the equivalent to 3% of the world’s population in 1940. The Soviet Union suffered most of all, with 26.6 million casualties, whilst German dead and missing numbered 5.3 million. The combined total of military dead is estimated at between 21-25 million personnel. Many, however, still lie in unknown graves. The Netherlands, of course, was fought over in 1940, when Hitler launched his Blitzkrieg against the West and again during the Allied liberation of enemy occupied Europe in 1944/45.

ABOVE: Lieutenant Geert Jonker, Commanding Officer of the Royal Netherlands Army Recovery & Identification Unit, and Dilip Sarkar at the Soesterberg laboratory in May 2016.

Consequently, the remains of the long-dead soldiers from those battles of yesteryear are still discovered across the Netherlands. Lieutenant Geert Jonker commands the Royal Netherlands Army Recovery & Identification Unit, working out of a small facility at Soesterberg:

“I have been involved with this important work since 1989 and did my first dig two years later – the recovery of Private Frederick Harrington, of Onibury, Shropshire, who was killed fighting with the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry. Our Unit was established in January 1945 under the Dutch Free Forces of the Interior, when half of Holland was still occupied and became part of the Ministry for War in August 1945. Today, we work on around 40 cases annually and are responsible for the recovery and identification of missing Dutch civilian and military personnel and both Allied and German personnel – this is still something that that the Dutch government considers both a duty of care and a debt of honour”.

As time marches on, bones and identity discs decompose, making the task of identification harder still but as Olga says ‘The best way to honour the dead is give them back their identities’.

Physical recovery of human remains, however, is just the start of a long process for Geert and his small but dedicated Unit: “What we have to do is combine military history with forensic archaeology and physical anthropology. Identification is frequently very difficult, and can take anything from just three days to over a decade. Oxygen and strontium isotope analysis of tooth enamel can confirm where in the world an individual came from and DNA, essentially genetic fingerprinting, can confirm beyond doubt the link to a known living relative.

Dental records, however, are crucial evidence, but we still need luck because many were destroyed and not preserved with army service records. Successfully identifying a casualty’s remains, providing families with closure at a military funeral, however, is the ultimate reward, making all the time and effort involved completely worthwhile”. Geert estimates that two thirds of cases concern German casualties. 140 British airborne soldiers, however, remain missing from one battle alone: the ill-fated attempt in September 1944 to seize the Rhine Bridge at Arnhem.

Thanks to the Royal Netherlands Army Recovery & Identification Unit, that number has reduced and will hopefully continue to do so. As is widely known, the ideological and cataclysmic clash between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union was fought on the Ostfront with unprecedented fury and without quarter. Across Eastern Europe and Russia, four million Russians and two million Germans remain unaccounted for. Since the Cold War’s peaceful conclusion, the Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge (German War Graves Commission) has recovered 40,000 missing casualties for reburial annually from the East.

Although appropriately reburied, the identities of most are never confirmed and such is the task’s enormity that only sites expected to yield at least fifty individuals are searched. Perhaps unsurprisingly, considering that memories of Nazi terror and genocide remain acute, the German archaeologists experience hostility from locals even today.

‘White Diggers’

Geert Jonker and team excavating the remains of a missing German soldier found in a former slit trench, half way up an eight metre high embankment on the Arnhem-Nijmegen railway line, just south of the Rhine and east of Driel.

The scale of loss and sacrifice is also deeply moving for young people such as Olga Ishniva and her friends. A reporter for the BBC Russian Service, living in England, Olga first went on gruelling expeditions recovering the Russian war dead from the vast forests around St Petersburg when at university.

Olga’s self-funded volunteer group ‘Exploration’ recovers casualties sympathetically and works hard on the research necessary to identify them. There is very little financial help from their government, although appropriate military funerals are provided. As time marches on, bones and identity discs decompose, making the task of identification harder still but as Olga says ‘The best way to honour the dead is give them back their identities’.

The work is arduous, in challenging physical conditions – just reaching the excavation sites entailing a 24-hour journey in an old army lorry. The activity is also dangerous for these ‘White Diggers’: live ammunition, including calibres of all sizes and grenades, are a constant and very real, ‘life-threatening’, hazard. It is, however, inspirational to know that young people, unborn at the time of the terrible events concerned and largely unsupported financially by the authorities, are so committed to this

The scale of loss and sacrifice is also deeply moving for young people such as Olga Ishniva and her friends. A reporter for the BBC Russian Service, living in England, Olga first went on gruelling expeditions recovering the Russian war dead from the vast forests around St Petersburg when at university.

Olga’s self-funded volunteer group ‘Exploration’ recovers casualties sympathetically and works hard on the research necessary to identify them. There is very little financial help from their government, although appropriate military funerals are provided. .

ABOVE: The excavated remains – a 19-year-old – of 116 Panzer Division Windhund, 1 Kompanie, Panzer Grenadier Regiment 60. This was part of the blocking force between units of the British 129 and 130 Infantry Brigades, 43 Wessex Division, during XXX Corps’ effort to reach Arnhem Bridge in September 1944.

The work is arduous, in challenging physical conditions – just reaching the excavation sites entailing a 24-hour journey in an old army lorry. The activity is also dangerous for these ‘White Diggers’: live ammunition, including calibres of all sizes and grenades, are a constant and very real, ‘life-threatening’, hazard. It is, however, inspirational to know that young people, unborn at the time of the terrible events concerned and largely unsupported financially by the authorities, are so committed to this crusade.

The integrity of this work is also a complete contrast to the so-called ‘Black Diggers’ who loot war graves to profit via online sales. As a historian, my personal motivation has been about the scale of loss and suffering, finding the stories of casualties beyond words. For many years, I was heavily involved in aviation and other military related archaeology and served as a police detective, professionally engaged with investigating violent, sudden death and forensic science.

Above: The remains of a German panzer grenadier cleaned and awaiting identification.

Naturally, therefore, that there still remain so many unaccounted for from the Second World War and that there is ongoing work to find them is of great interest to me. As a modeller, I felt compelled to create a 3D artistic interpretation of the subject. This is far from ghoulish or in any way disrespectful and insensitive. On the contrary, the intention of this somewhat unusual model is to provoke thought and debate, raising awareness of this highly emotive but still unresolved issue.

ABOVE: The horror of the Ostfront – this photograph taken by Olga Ivshina on a recent expedition recovering war dead from Russia provides a graphic idea of the extent of work still to be done.

How the model was made

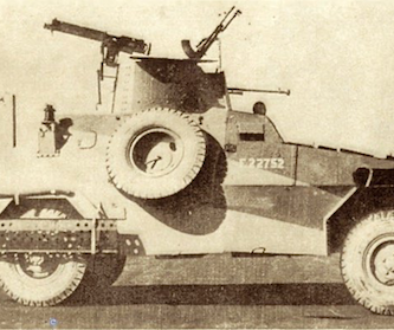

There were certainly no footprints ahead in the snow for this creation! Consequently, the whole project required an immense amount of research and planning. I decided to depict a German soldier for no other reason than that I have always been fascinated by the stahlhelm’s shape and have a collection of rusty ones, including two I brought back from fascinating trips to Poland and Lithuania.

Research, as ever, is key and the internet abounds with useful images. These were hoovered up, printed out and stuck around my work bench, the area ultimately resembling our old CID office! When such human remains are found in reality, there is frequently little that is obvious and immediately recognisable. Because in this case the human eye needed to instantly connect with the image presented, a little artistic licence was required.

To achieve the required impact it was necessary to go large. Thankfully, although the 1/6 Airfix skeleton is no longer in production, examples are still obtainable…

Photo 1:

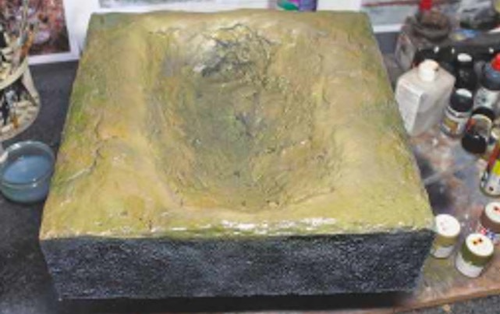

To achieve the required impact it was necessary to go large. Thankfully, although the 1/6 Airfix skeleton is no longer in production, examples are still obtainable via eBay and fellow modellers’ stashes. The interest in this particular scale of action figures also meant that accurate weapons, ammunition and field gear is readily obtainable. Because the skeleton needed to be placed in a hole or depression, I obtained a large block of polystyrene (used as a wedding cake tier blank), 350mm square by 100mm high.

It was next necessary to use a breadknife, Stanley knife and spoon to cut and gouge out the hole. Then, some thought was given as to how and where the skeleton and accoutrements would be placed in due course. Due to the rigid plastic spine, there are limitations regarding the attitude the skeleton is shown at, although next time, I may section and articulate the spine by threading the pieces onto wire.

The other issue, compositionally, is that a skeleton being excavated is not necessarily visually appealing, or even immediately recognisable, given decomposition and disintegration. The human eye in this context, however, needs to see something instantly recognisable. Moreover, an MG42 is an impressive weapon, so I wanted to show it in its entirety and not partially buried.

The composition also poses a question: have these remains been partially excavated or simply left in situ and forgotten?

Above: Live ammunition is a constant worry for Olga Ivshina’s team – the BBC Russian Service reporter pictured here with a large calibre shell in August 2016.

Certain items of field equipment, such as canteens and water bottles, do not rust, being made of aluminium. These were brush painted with Tamiya Chrome Silver X-11. When dry, these items were brushed with AK Heavy Chipping Fluid. Then, the cup was painted Tamiya Dark Grey XF-24, the canteen Tamiya Field Grey XF-65. Using a stiff brush and water, these colours were rubbed away to simulate wear.

The felt covering on the water bottle was distressed with sand paper. The other items were then undercoated with AK Interactive Rust. Various thick coats, working light to dark, of AK Brush & Airbrush colours were then slapped on, mixed with a little sand, to simulate crusted rust. These were Chipping Colour, Shadow, Old Dark, Medium and Light Rust.

Various AK washes, including Dark Rust Deposit, Medium Rust Deposit, Light Rust and Streaking Grime were used on the other parts, along with burnt umber oil wash.

The trick here is not to use too much pigment from the bottom of the jar, or stir the pot, just keep washing using the enamel from the top, keeping the colours and layers very thin. There is no need to let it dry and blend because so little pigment is used. Just keep washing and let it all run.

The skeleton was then treated to some coats of Tamiya Desert Yellow XF-59 and Wooden Deck Tan XF-78, then lightly dry brushed with Buff XF-57 and a tiny bit of Vallejo Ivory. It was then given an oil wash of Burnt Umber, as were the non-rusting items.

The whole thing, in any case, will be weathered together into the final diorama because everything needs to look like a cohesive whole with nothing appearing to be stuck on as an after-thought.

Because laces, like clothes, decompose, the mouldings of these were removed from the boots, which, after first grey then black primer, were distressed a little and treated to various dirty coloured AK washes, such as Streaking Grime, and Burnt Umber oil wash. This actually made some colour run from the soles but accidentally looked realistic, like the dye having faded and rotted.

A bit of rust wash on the soles, to replicate rusting steel parts, completed the base. Other items were treated with AK pigments, including Burnt Umber, Dark and Track Rust, all dropped on to the parts with a teaspoon and fixed using ordinary white spirit. The pigments help to create a realistic scale texture. The whole lot was then washed again with burnt sienna and burnt umber oils.

With the skeleton and other parts sufficiently base-painted ready to fix in place and finish off as part of a cohesive whole, it was time to start work on the diorama.

This was first given a layer of white glue, followed by a coating of Polyfilla. This was done roughly, providing a key for the forthcoming second layer.

When the first layer had thoroughly dried, the second went on smoother and was then undercoated, first with Halford’s grey primer, then sprayed with AK Black Primer. Tamiya Flat Earth XF-59, Khaki XF-49 and Dark Green XF-81 was then variously over-sprayed.

Little or none of this will probably be seen in the end result, so this is another base to work from.

Having decided on the skeleton’s attitude, the helmet and skull is first fixed in place, then the rest, in sections. This is then made a part of the diorama through blending it in with Polyfilla, which covers some bones.

The front of the rib cage, however, notwithstanding the ‘artistic licence’ involved, will not be fixed in place – rib cages collapse and intact ribs would appear too unrealistic. These will be added later, in pieces.

Dark Earth, Dark Mud and Europe Dust, are mixed with plaster, sand and Mig Acrylic Resin Fixer. This gooey paste is then spooned around and inside the skeleton, to blend it properly in.

Photo 15 – 17:

The rib cage front is cut into appropriate pieces which are set within the gooey resin. The other parts are fixed with super glue. Various grades of sand are sprinkled over the diorama to create texture fixed in place with AK Gravel & Sand Fixer, applied with a pipette. A bit of dry moss that fell off our roof was crumbled up and stuck around the edge. Ignore the colours at this stage; we are just trying to create textures.

I’d not made grass before, so this was another venture into the unknown. In my mind’s eye, the scene I pictured was a sandy area with sparse clumps of tall grass, perhaps growing back as nature reclaimed the site. Using Woodland Scenics ‘Harvest Gold’, I held it together in random lengths, around each clump of which I tightly wound fine fuse wire before cutting it down and dabbing it in Superglue.

Holes were then drilled into the base, filled with medium Superglue and the clumps stuck in. Some were painted green using various shades of thinned Tamiya acrylics. Some Woodland Scenics ‘Underbrush’ was also stuck down using white glue. This and the grass needed toning down, so I did this with dirty white spirit/burnt umber oil wash poured over the base using a pipette – a great method.

I also started building up the ground by shovelling on pigments with a teaspoon and fixing with white spirit, again using the pipette. AK ‘Sand & Gravel Fixer’ would have been better, I suspect, but I knocked the bottle over! The pigments used were Mig Dark Earth and Europe Dust and AK Burnt Umber.

Again, the piles of powder were given the dirty white spirit and pipette treatment. Using air pressure, the pigmented fluid can be made to run, finding its own way down into the hole – and, as anyone who has ever dug a hole knows, there are often all kinds of textures and colours.

The next step, after the pigment and washes had dried, was to soak on AK washes, again using the pipette. I kept topping up the bottles of washes with AK Odourless Thinners, giving it a good shake.

These thin, translucent washes were then poured over the terrain, working from dark to light with the pipette. The washes used were AK Sand Yellow Deposits, Light Dust and Brown Earth Deposits.

Photo 21

A week later and we can see what appears to be a transformation. What has happened is that the soaked diorama has thoroughly dried, the colours of the washes, particularly the light shades, having come through perfectly. The boots were lightly brushed with Vallejo matt varnish and the skull dusted with the dry powder left on a brush, then buffed using a finger, removing the excess and highlighting raised facial features. I guess you can go on and on with these things and, seriously ‘hats off’ to these ‘Extreme Realism’ artists, but by this time I felt that the job was done and that there really wasn’t anything else I could add to the ensemble. There is always a danger of overworking a model and the trick is to know when to stop!

Conclusion

Because of the size, it is an imposing piece, so I decided, the best way to display it was in a topless wooden box. Facebook friend Mark Ayling very kindly organised this for me via a cabinet-maker colleague and, with the addition of a plaque from ‘Nameplates for Models’ (excellent customer service!), job done. Is it a model or is this art? I’m not sure, so you decide. It was a very interesting and, possibly unique, thing to make, especially in 1/6 scale, during which process I learned a great deal. As previously explained, there is actually a serious message behind this diorama which might just make us all think about what war and military machines are really all about. Spare a thought for those still missing from conflicts all over the world, regardless of their nationality or politics.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to:

Lieutenant Geert Jonker,

Olga Ishniva,

Mark Ayling,

John Fidoe,

Andy Long,

Chris Gale

and, as ever, my long-suffering wife Karen.

Reproduced with kind permission of Doolittle Media – www.adhpublishing.com/

and the author Dilip Sarkar MBE – www.ourfinesthour.net/contact/

First published in Military Modelling 2017