ARMOURED CARS IN THE DESERT

British A/Cs in NorthAfrica in WW II.

by

John Sandars, (B.M.S.S M.A.F.V.A)

MUCH has been written about armour in the North African Desert during World War II, but most of it has been about tanks and little has been said about the armoured cars which, despite their relatively small numbers, also played an important part in the campaign. It is the aim of these articles to show how they operated, which regiments used them, and also to give some tips on modelling a particular type of car.

Both German and Italian armies used armoured cars as part of mixed units with other arms. In the Wehrmacht they formed part of the Panzer Divisional guns, while the Italians had a few to stiffen their motorcycle rifle battalions. We, on the other hand, apart from a few among the carriers and light tanks of the infantry divisional cavalry regiments, used our armoured cars on their own in complete regiments, as the main reconnaissance elements of our armoured divisions.

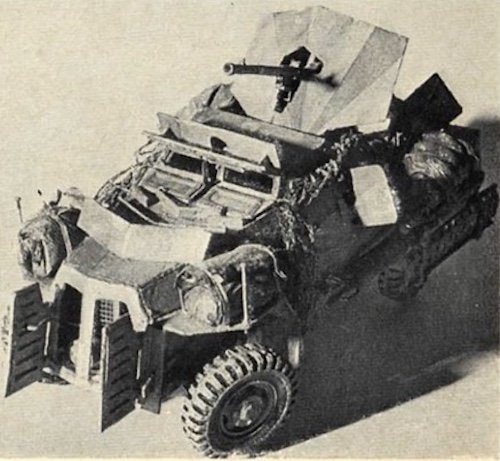

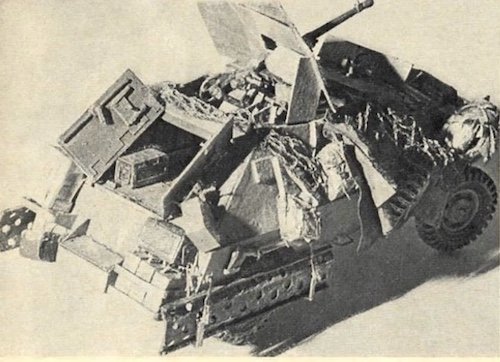

The author’s scratchbuilt 1/35th scale Marmon-Herrington Breda car with “butterfly”‘ gun shield-which rotated with the weapon but did not elevate with it.

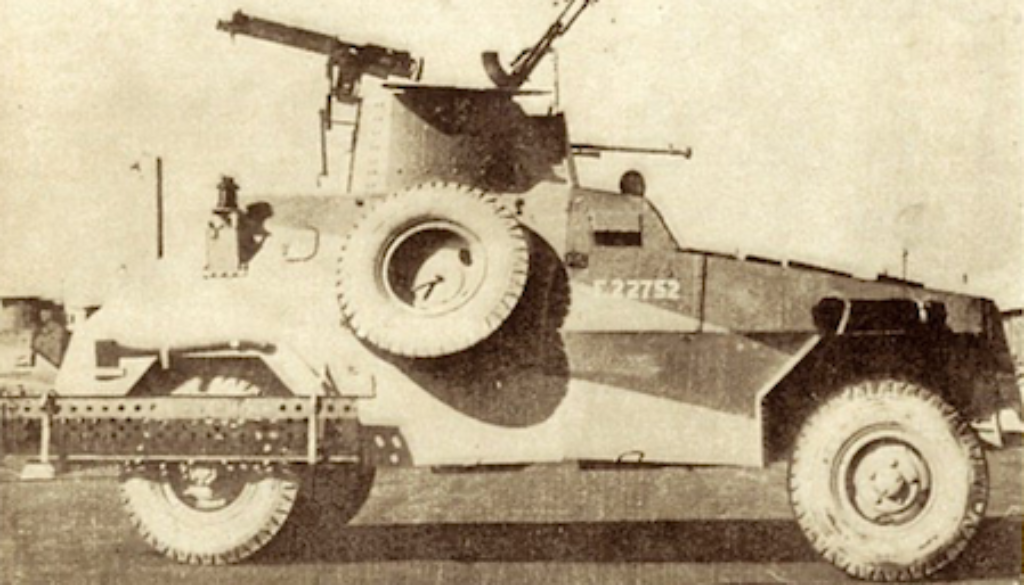

Marmon-Herrington Mark 2 with its normal armament of Boys anti-tank rifle, Vickers machine gun and two Bren guns. Note camouflage pattern-which extends to spare wheel! “Monkey-Harry” dimensions were w.b. 11′ 2″, track 5′, o.a. length 16′, o.a. width 6′ 6″, height T 3″ (to turret top).

Photo: R.A.C. Tank Museum, Bovington.

Organisation

These armoured car regiments were a mixture of English regular cavalry units and South African Tank Corps. The number in the desert rose from one in 1940 to ten regiments at the end of the campaign in 1943, and as time went by and experience of desert fighting was gained. their organisation was altered. In 1939-40 a British regiment consisted of an RHQ and three so-called sabre squadrons, each of three troops of three cars, giving an overall total of about thirty AFVs.

By the start of the war against Italy it was obvious that this was insufficient for the wide expanses of the desert and a fourth troop had been added to each squadron; this was followed by a fifth troop and some extra cars in regimental and squadron HQs by mid 1941, to give regiments of 58 cars. This organisation lasted until early 1943 when the move away from open desert began to show the need for other vehicles as well as armoured cars. First troops of jeeps began to be used or special tasks, then 6 pdr. Deacon SP anti-tank guns were attached to squadrons for varying periods. Before leaving Africa regiments underwent a major reorganisation to make them more suitable for use in Europe; each squadron was split into six troops; four of these each consisted of a pair of armoured cars and a Dingo scout car, the fifth had four White scout cars to form a support troop with mortars and pioneers, and the sixth was a troop of three jeeps.

Later still in Italy half tracks mounting 75mm guns were doled out in pairs to regimental HQs, and at least one regiment formed an unofficial horse troop for use in the mountains. The South Africans worked on roughly the same l:nes, having armoured car regiments like ours, and reconnaissance battalions with three armoured car companies and a motorcycle company. The former were usually employed with our armoured divisions while the latter, which had 38 armoured cars each, spe!’lt most of the time with their infantry, but this was not always the case and they were swapped around quite a bit from time to time.

Units

The first two British cavalry regiments to exchange their horses for armoured cars back in the 1920s were the 12th. Lancers and the 11th. Hussars. These two regiments alternated in the Middle East until the early 1930s after which the 11 th. Hussars remained there from 1934 until the end of the fighting in North Africa in 1943. Although the ‘cherrypickers’ of Balaclava fame did not get much opportunity of showing off their distinctive trousers in the desert they did have a unique type of rust coloured beret with a crimson band, known irreverently by some, as cowpatsl Until the war their time was divided between Egypt and Palestine, and they soon became the acknowledged experts on armoured car matters in the desert, devising their own tactics and instructing other units in them when they arrived in the theatre. Next on the scene were the King’s Dragoon Guards, who had been mechanised as a light tank regiment in 1937, only to be converted to armoured cars, supposedly as a temporary measure, when they arrived in Egypt at Christmas in 1940, just in time to have one squadron fight alongside the 11th. Hussars at Beda Fomm. Shortly after this the Royal Dragoons, who had been part of the horsed cavalry division in Palestine also mechanised in Egypt, coming to the desert as an armoured car regiment in early 1941. They, like the 11th. Hussars, had their own distinctive head gear, in this case a grey beret, and their regimental badge of a somewhat germanic eagle caused confusion to both friend and foe on occasion.

By August 1941 the 4th. South African armoured car regiment had arrived, to be followed in due course by the 6th., and the 7th. and 3rd. Reconnaissance battalions. In November the 12th. Lancers returned to the Middle East after service in France, leaving a small detachment in London for Royal and VIP escort duties and finally in mid 1942 the remaining horsed cavalry from Palestine came to Egypt to be formed into the Household Cavalry armoured car regiment. In fact one other regiment of armoured cars appeared right at the end of the campaign but played no real part in the action in that role, when the 8th. Hussars were temporarily converted from tanks. These units were not normally all in action in the desert all the time. Whereas other arms tended to either be in action, or out of direct contact with the enemy, the armoured cars were always in touch with the foe, so units had to relieve each other at intervals so they could rest and re-equip, in many cases handing over their cars to the relieving regiment at the front and drawing new ones later in Egypt. In addition to this, regiments were at times used elsewhere in the Middle East; the 11 th. Hussars were out of the desert in Persia and Iraq from the end of 1941 until mid 1942 while the Royals spent the second half of 1941 in Syria. During 1940 however both the 11 th. Hussars, and later the KDG were augmented by a squadron of RAF cars.

Equipment

Equipment

At the start of the campaign the 11 th. Hussars had a mixture of 1920 and 1924 pattern Rolls Royces and Morris AC9s. Shortly after the outbreak of hostilities the Rolls had their closed turrets with their ball mounted Vickers machine guns replaced with open topped ones mounting Boys rifles, bren guns and smoke projectors, similar to those fitted on the Morris. Performance of both types was improved by the fitting of special desert tyres, but with two wheel drive neither was ideal for desert conditions. Initially only the Morris was fitted with radio, and so tended to be allocated to troop leaders and squadron HQs.

Although the Rolls was phased out in the spring of 1941, there were a few Morris still in use in the middle of the year. The next vehicle was the Marmon Herrington Mk ll, a large clumsy car with a four man crew, built round a Ford chassis and engine by the South Africans. and used both by British and South African units. It had four wheel drive, but suffered from easily broken springs and a tendancy to overheat in a following wind; with thinner armour than the Rolls and Morris and no more armament except a Vickers gun on an AA mount it was not much of an improvement, but its main redeeming feature was apparently the fact that it invariably started first go, which must have been comforting for crews faced with the more formidable German vehicles! The first MHs were issued to the K DGs in January 1941.

On the suggestion of the 11 th. Hussars some had the tops removed and captured Italian 20mm Breda light AA guns fitted to give them more punch; eventually most regiments had some of these ‘Breda cars·, usually in squadron HQs. The Royals also received MHs in early 1941, but the first batch were quickly emoved from them to re-equip the 11 th. Hussars during the flap caused by the Afrika Korps’ first offensive. The South Africans brought their own cars with them, distinguished by serial numbers beginning with a U instead of the F used by the British. In November the 11th. Hussars were equipped with Humbers and the 12th. Lancers were already equipped with them when they arrived. These cars were armed with a 15mm Besa gun, and were the first ‘wheeled tank’ as opposed to ‘armoured motor car· type of vehicles to be seen in the theatre.

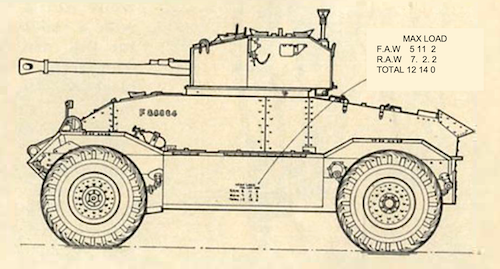

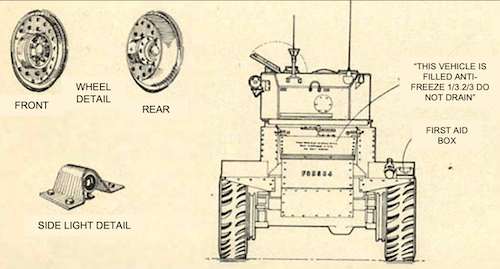

They seem to have been mostly Mk II vehicles with a few Mk Is and although they were a distinct improvement on the MH, they were rather underpowered and only had an engine life of 3000 miles. At about the same time the Royals and the KDGs (except for one squadron shut up in Tobruk) were reequipped with MH Mk Ills, a slightly improved version with a shorter wheelbase than the Mk 11, but still the same armament. By the middle of 1942 this had become such a drawback that units were unofficially removing the turrets of their MHs and fitting captured German 37mm, or Italian 47mm. guns, as well as the occasional 2 pdr. or French Hotchkiss 25mm. A better remedy arrived shortly after in the form of the Daimler armoured car with its 2 pdr. gun, thicker armour and superb cross country performance; at last we had a car that was superior to the German equivalent, but at first there were only enough for one car per troop, and so the KDGs and Royals who received them in mid 1942 had mixed troops of Daimlers and MHs.

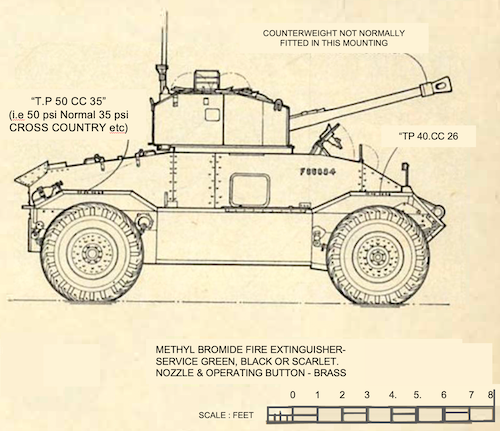

The 11th. Hussars stuck to the Humber, getting the improved Mk Ill also in the middle of 1942 while the 12th. Lancers had theirs replaced by Daimlers in March 1943 although they kept some Humbers, which were later replaced by the Mk IV with an American 37mm gun, in the RHQ and SHQs as they were roomier than the Daimlers. The last type of car used in North Africa was the AEC, a hefty diesel engined vehicle with a Valentine tank turret mounting a 2 pdr. gun, and capable of a 200 mile radius of action. A few of these cars went to the KDG and the Royals in early 1943. The official policy seems to have been to use them as a heavy support troop, but in practice the KDG at least, who had just swapped their Daimlers and MHs for Humbers, found it better to split them up so that each troop had one of these monsters. The South Africans kept their MHs until the end of the campaign, the MH Mk. IV coming along just too late to take part.

Tactics

One of the first indications that the Afrika Korps had arrived in the desert was a minor collision between a car of the KDG and a German 8 wheeler on a desert track at the end of February 1941. It was dusk and both sides were so surprised that the only damage done was a bedroll torn off the MH as it scraped past the German. In general however, due to the inferior armament of our cars, close contact was avoided and information was gained by observation rather than fighting, once the Germans had taken over from the Italians. In static periods the armies were usually many miles apart, and our armoured cars would establish continuous patrol lines to report any enemy activity.

Squadron HQs would be positioned up to 20 miles ahead of the main body of allied forces and would have their sabre troops in line some 10 miles further ahead still. Sometimes these lines stretched for over fifty miles; if the ground was flat and the number of armoured cars sufficient they would observe from static positions, but if not they had to move about to cover their area, and this made them more likely to be seen and attacked by enemy aircraft. Exposed observation lines of this type were often supported by small – groups of other arms, as at Gazala in early 1942 when i2th. Lancers had a company of the Guards and, of all things, 8 Valentine tanks, with them. The normal drill for keeping observation in this way was to have 3 troops in the line, and 2 back with SHQ resting and maintaining; a fresh troop relieving one in the line every day.

Regiments were usually allocated on a scale of one to each armoured division, although sometimes more were used, and at others, as in operation Crusader, they worked for individual armoured brigades; in any case, at least in defence they tended to link together to form lines of observation for the army as a whole. In the advance they scouted ahead and on the flanks of the main body, and in addition to reporting any enemy sighted they often gave details of the ‘going’ which enabled the best route to be picked for the bulk of the force. Owing to the weak armament and lack of integral infantry and artillery of our armoured car regiments, for most of thll campaign they were seldom dble to bounce the enemy out of weak positions on their own, as the German recce units did, and at least until late 1942 they had difficulties driving in the enemy’s armoured car screens to see what his main body was up to. During actual battles the armoured cars hovered on the wings, following and reporting groups of enemy vehicles, and looking for opportunities to attack unescorted soft vehicles.

Raiding into the rear of the enemy lines was also an important part of their role. In the early days when the Italians formed the only opposition the armoured cars regularly operated for long periods behind their lines, and beat up their desert forts, such as Maddalena, and their supply convoys almost at will. It’ was the 11 th. Hussars who started the ball rolling by crossing into Libya on the first day of the war with Italy and firing the first shots of the whole campaign. Later, at Alamein two squadrons of Royals and two of the 4th. SA armoured car regiment were the first troops to break out, and they spent several days creating havoc among the enemy administrative units before the retreat began and they were joined by other friendly forces. On other occasions composite columns of armoured cars, guns, motor infantry and sappers were formed for specific tasks, such as the capture of airfields during the advance after Alamein, but unlike the German recce units, these were ad hoe formations that were disbanded as soon as their job had been completed.

In addition to all this, ·c· Squadron of the KDG remained in Tobruk through out the siege and eventually lead the breakout during operation Crusader. Despite their general lack of offensive power a considerable amount of enemy equipment was captured by armoured car units. The first Stug. Ill seen in the desert was stopped by some up-gunned South African MHs near Bir Hachiem in 1942, while the first Tiger encountered by 7th. armoured division in Tunisia surrendered, albeit having suffered some damage, to a car of 11 th. Hussars. Even in quiet periods life was pretty tough for armoured car crews, with a regular diet, when in the line, of bully beef, biscuits, milk tea and sugar only, with delicacies such as jam, tinned butter, tinned fish, tinned bacon and ‘soya link’ sausages being much sought after, but seldom available in any quantities. Water was normally rationed to t gallon per man per day for all purposes, including the car’s radiator, and there was always the danger of air attacks. These were probably the greatest cause of casualties, and despite parking anything up to 400 yards apart in daylight and the use of Breda cars, the armoured car regiments really had no effective answer to straffing and bombing. In addition to this the Italians sometimes dropped small landmines shaped like thermos flasks in areas where cars were known to be operating.

Administration and Signals

Operating continuously so far ahead of the main forces, armoured cars had to use a rather different system of resupply to other units .. This was initially devised by 11th. Hussars and later adopted by other regiments, with or without minor alterations. Supply vehicles were split up into three echelons called B 1, B2, and B3, (Unlike the A and B echelons of tank units). The B1s consisted of groups of half a dozen vehicles at SHQs under the command of the Squadron sergeant majors consisting of petrol and fitters lorries, first aid truck, and a signals truck with spare batteries.

The B3 was the bulk of the supply lorries, usually controlled by RHQ, and positioned several miles behind it, and it was from this echelon that squadrons were replenished each whenever possible. The B2 echelon was a group of B3 vehicles detached to actually take the necessary stores up to the squadrons. A single squadron with its echelons in 1941 would consist of about 40 vehicles and 120 men, while the B3 echelons for a whole regiment would be over 100 vehicles. Regimental petrol lorries could each carry about 500 gallons, and to give an idea of the size of the administrative problems that sometimes had to be faced, when 12th. Lancers with a few guns and infantry were sent on a six day raid they required an echelon of 240 lorries. Recovery was also a problem, and regiments seem to have used Matadors as well as the heavier Scammells for this.

Because reporting was their main function armoured cars had a much greater need for continuous wireless communication at all levels than other units, and therefore they used more ‘nets’, having separate frequencies for rear link, the regiment, each squadron and the echelons. They had no Royal Signals personnel attached, but 11th Hussars and possibly other units trained their bandsmen to be expert signallers. Initially only one car per troop had wireless, and this was either a No. 9 or No. 11 set. It was not long however before all cars were fitted with sets and in early 1942 the more modern No. 19 sets became available.

Modelling

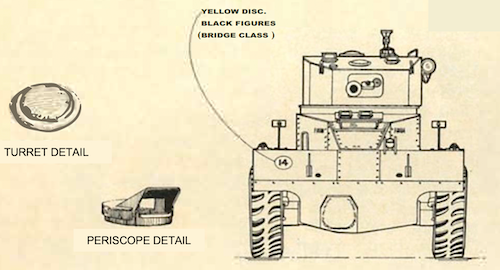

Kits of British armoured cars are still few and far between so there is plenty of scope for the scratch builder, as can be seen from the illustrations. I am therefore finishing up with details of a 1/32 scale group built round a scratch- built Marmon Herrington Mk II Breda Car.

These cars, unlike the later Mk. Ills were officially modified in base workshops to take the captured Italian guns. This involved the removal of most of the car’s roof and altering the top of the side armour to widen the car in way of the mounting so that the gun, and its large British made shield, would fit in on what was probably some form of pedestal. The guns seem to have had their sighting gear and the training handwheel removed, but to have retained the elevating wheel; elevation was in any case limited by the shield which did not move with the gun, but was welded to the mounting. The car which the model is based on is one of the latter all welded models with the side doors set further back, and the spare wheel lower down and further forward than on the original version. It also has extra locally added armour in the form of an enlarged bullet splash deflector on the bonnet, and an extra visor that doubles as a gun barrel clamp over the windscreen.

Information for the model was taken from photographs and books, including pictures in George Bradford’s Armour, Camouflage and markings, North Africa 1940-43′, and the revised edition of Bart Vanderveen’s Observers fighting vehicle directory the general dimensions and shape, of the car were taken from a drawing by S. R. Cobb, and Gerald Scarborough’s article on the MH II in the May 1972 Airfix Magazine.

Starting with the base; this was made by mixing sand sieved through fine curtain netting with flour and water, and spreading the resulting paste onto the underside of a lino floor tile. This was then sprinkled with dry sand and the wheel tracks and footprints were impressed into the surface before it set. Small pieces of moss were also planted in the sand to represent clumps of camelthorn. The sand and flour set like concrete and the figures could then be glued to it. The finished base was edged with balsa wood, but this sort of mixture can also be packed into an upturned box lid, which gives ready made edges that can be painted.

As the car was to be fixed to the base no underside detail that would not be visible was made; the floor was glued direct onto a simple rectangular frame of 3/16 in. balsa, and the axles, of t in. dowel with built up differentials, were fastened to the underside of this frame. Bits of balsa block were also attacher! for the sump and petrol tanks (just in front of the rear wheels) where they were visible below the armour. The wheels were cast in epoxy resin using individual Plasticine moulds and a master wheel as a pattern (See Military Modelling, October 4, p.589 for details of method).

This method can be taken a step further, I am told by Stuart Fanshaw of MAFV A; if you cast a single wheel in a Plasticine mold you can then use this as a pattern for making a rubber mold, since the epoxy resin wheel will not melt in molten rubber but the original plastic one will. A rubber mold can of course be used for as many wheels as you want, unlike a Plasticine one which will only do a single casting.

The hull of the car was built up from panels of cardboard glued together with Evo-Stik; this is comparatively easy as the whole vehicle is made up of flat surfaces, without any awkward curves; plastic card would do just as well for those who use it. Curtain net gauze was used for the radiator, and transparent plastic for the two small folded-down windshields. Having little information on the interior I deliberately arranged the figures in the group to prevent too good a view in through the top or rear doors. Seats, steering wheel etc., were put in at the front, and racks of ammunition boxes over the wheel arches at the back, with an inward facing seat at the left rear, where the wireless operator sat in the unconverted cars. Plastruct T bars was glued to the insides of the joins between the hull plates to represent the mild steel frame to which the armour was attached in the original.

A first aid box, tommy gun and some loose trays of 20mm ammunition completed the internal arrangements, positioning being by guesswork. The gun was made up from hardwood rod and balsa on a cardboard cradle. Cocktail stick trunnions allowed it to elevate within the limits of the shield which was fixed to the cradle, and a pin pushed down into the pedestal through the base of the mounting allowed it to train through 360°. The pedestal was a length of ¼ in. dowel glued to a plate on the deck with four supporting cardboard webs. The elevating handwheel was fashioned by bending a length of 30 amp. fusewire around a piece of dowelling to form a ring, and then gluing plastic card rod spokes to it; the whole being coated with Unibond to bind it together.

When the car was completed and painted the various items of kit were attached to the outside, and draped around it; the camouflage net was a hair drying net; the bedrolls and packs, Plasticine covered with typing paper and tissue; the greatcoat was paper and the tin hat, boots and stretcher were bits from plastic figures and kits. The pick and axe were from the spares box and were left overs from some kit, make forgotten; the ammunition boxes and water tins were wood and card coated with a couple of coats of Unibond to give a pressed metal look; the bully beef crate, ( Libbys) and one of the boxes in the rack on the back of the gunshield were made of balsa and left natural wood colour.

The figures, as can be seen from the pictures, were made up from bits cut off 1 /32 scale Airfix polythene models; these were dowelled to each other with plastic card rod and glued with UHU, before having the gaps filled in with ‘Greenstuff’ and paper battledress blouses, greatcoats etc added. The corn leted figures were coated with Unibond before painting.

There were several colour schemes used by armoured cars in the desert; before the war a sand colour with broad red irregular bands over it was used by 11th. Hussars. By late 1940 tapering stripes of sand, blue/grey and dark brown or green had generally been adopted, and later on in 1942 this seems to have been replaced by either overall plain sand, or sand with large patches of some dark brown or grey colour. In about April 1943, when the link up with 1st. Army was imminent an overall dark green, more suitable for the more cultivated areas of Tunisia, was adopted. As cars were probably seldom repainted after initial issue, and were in any case swapped about between units, it is not possible to be very specific on dates for colour schemes. The model has been painted in the tapered stripe pattern with Humbrol desert yellow mixed with their concrete colour; dark earth, and blue mixed with slate grey and white.

People often argue over colours, but it seems likely that some of the paint used was of local manufacture, shipping space from UK being scarce and at least one armoured unit being known to have used concoctions from a local cement works to camouflage its vehicles. It therefore seems a little pointless to be pedantic over exact shades. No markings were added except a vehicle serial number on the sides of the bonnet. This lack of markings would appear from photographs to have been fairly general for armoured cars.

Above: The author’s famous Marmon Herrington Mk 2 model.

Right: In 1 /32nd scale, a Daimler Mk 1, also by the author; The wheels of this model were turned up from broom handle and the tyre treads cut in with a saw.

The personnel were made and painted as South Africans (despite their car having an English number) with their corporal in the small rimmed sun helmet, and some of them with orange tapes on their shoulder straps, while the officer has the figure IV as the badge on his beret, as was worn by 4th. South African armoured car regiment. Faces were painted with yellow ochre, pillar box red, and Vandyke brown oil paints mixed with Humbrol white. The rest of the figures were painted with Humbrol and both they and the car were extensively dry brushed after painting. For the car a rust mixture of Humbrol Aluminium, orange, black and dark earth; a steel mixture of aluminium and black, and bleached teak dust were all used, while the figures were done with dust and a diluted brown/black general dirt colour.

Finally, although it was one of the points that had to be thought of first, the composition of the group had to be decided, and for this it was necessary to imagine what was actually happening. After several ideas. one with a young officer expounding some bright idea to the two rather sceptical members of the car’s crew, while the sergeant looks on, wondering whether he ought to interrupt ‘Sir’ before he makes a fool of himself, and the car’s driver returns with his spade from a visit to the far side of an adjacent patch of scrub, was chosen. This made a nicely balanced group with a bit of interest and at the same time fulfilled the requirement to partly obscure the interior of the vehicle.

REFERENCES

The Eleventh at War. Clarke. Michael Joseph 1952.

A day’s march nearer home. Rocksavage. Bumpus 1947.

History of the KDG 1938-45. McCorquodale. Privately printed.

History of the XII Royal Lancers. Stewart. Oxford 1950.

Profile Book 2. British & Commonwealth AFVs. Crow.

Profile AFV weapons 21 & 30.

Armour, Camouflage and markings, North Africa 1940-43 George Bradford

Observers fighting vehicle directory – revised edition Bart Vanderveen

Drawing by S. R. Cobb, Gerald Scarborough’s

Article on the MH II May 1972 Airfix Magazine Gerald Scarborough